The Mathematicians' Brief in Rucho v. Common Cause

MGGG has organized a collaborative effort of mathematical and legal experts to file an amicus brief for the upcoming Supreme Court gerrymandering cases. An amicus brief is a “friend of the court” filing, where outside parties try to help supply the court with useful information.

Read the mathematicians’ brief.

Backstory

The Court has clearly asked for an account of partisan gerrymandering that is based on harm to individual rights in specific districts. (That is, they are not currently receptive to arguments about overall statewide balance, and it’s not productive to focus on the abstract theory of representative democracy.) Relying upon and drawing from the Court’s prior precedents, we first articulated a legal conception of partisan vote dilution. We then explained why and how a mathematical technique can help courts identify and reliably prove the legal harm.

Here’s how our argument goes:

- Vote dilution is the intentional departure from a baseline of equal treatment of voters by the state. Some voters are harmed by having the weight, power, and value of their vote intentionally diminished by the government.

- This is unconstitutional, whether it’s done on the basis of geography, race, sex, or partisanship, and for the same reasons.

- When it comes to population balance, the arithmetic has not been that hard for the Court—the baseline is equal population in every district.

- When it comes to partisanship, the neutral baseline is harder to find. But there is a reliable, well-developed mathematical technique called MCMC that’s up to the job, and that scopes out how districts will tend to divide up a state if only the written rules are taking into account, and the voting patterns are held constant.

- A district that’s an extreme outlier is probably a gerrymander!

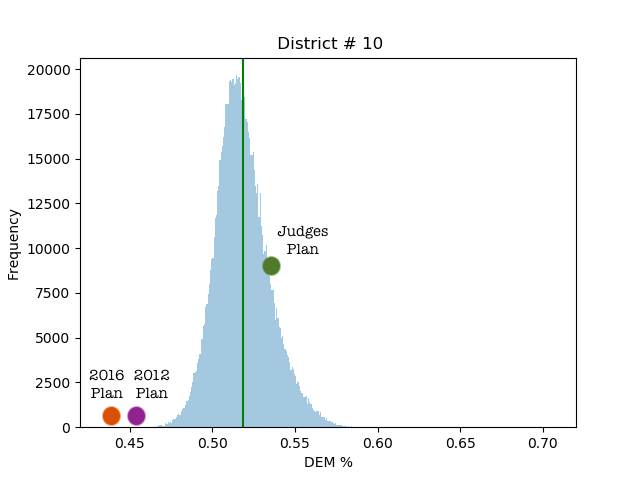

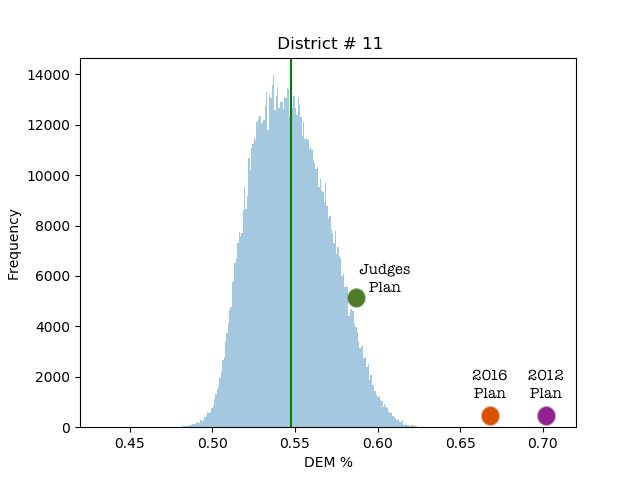

For instance, here are plots showing two North Carolina districts from the Legislature’s 2016 Plan. The bell curves are histograms of a million plans sampled by MCMC.

(2012 Plan and 2016 Plan were proposed and enacted by the NC Legislature. The Judges’ Plan, by contrast, was made by a bipartisan panel of retired judges.) In the 2012 and 2016 Plans, Democrats are “packed” or overstuffed into the right-hand district and “cracked” or dispersed out of the left-hand district.

Both enacted plans have districts so far outside the curve they look like they don’t even belong to the same universe of possibilities. We argue that this is better explained by partisan intent—getting a solid R district instead of two likely D districts—than by the rules and political geography of the state. We were able to replicate the outlier findings of the plaintiff’s expert very closely, even though we used a totally different MCMC technique.